Fertile Seeds as Our Livelihood: Taking Communal Action to Secure our Future

Kulturgutexpress 2014: True-to-seed varieties not a given, even in organic farming – Conservation of natural life requires research and commitment – Costs must be shared by all market participants

Seed development has experienced a reversal in the past decades: it is no longer the case that farmers and gardeners reproduce their own seeds, share them with others, and make them available. Instead, large chemical companies develop seeds in a laboratory, in a worldwide competition for money and rights. Such companies control around 90 percent of the seed market. Even in organic farming, F1 hybrids and even completely sterile CMS seeds have become the rule rather than the exception. Funding sources are needed to ensure the natural handling of seeds and preservation of life. This requires the equal commitment of all participants in the value chain.

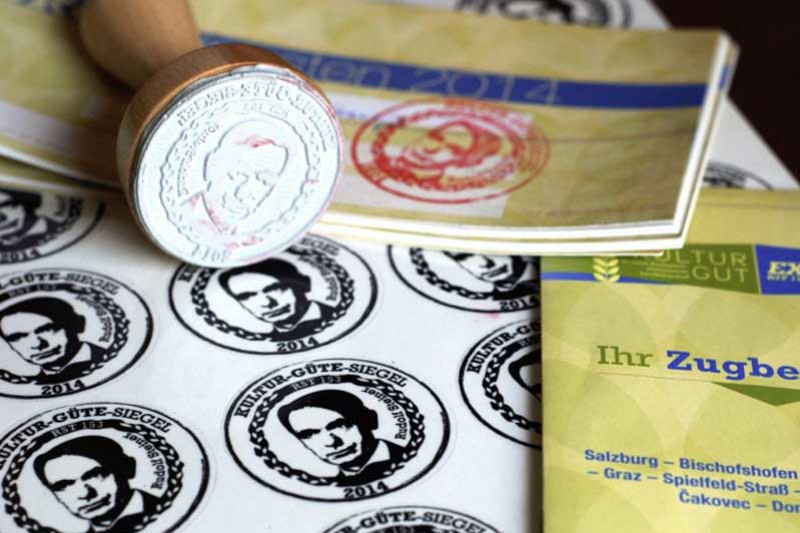

In a train called the Kulturgutexpress 2014, artistic and socio-dynamic methods were used to seek out and find new approaches to the topic of seed development. Various aspects of the topic were addressed in a podium discussion on board the special train.

Mara Müller of Arche Noah, an Austrian association for the preservation and development of crop diversity, emphasized that crop seeds are a cultural asset: “They developed in conversation between humans and plants. Culture and the needs of humans shaped crop seeds. It was a joint development. How processes are going at the moment, we are a long way away from passing on seeds as a form of culture, in this sense.”

Dr. Bertold Heyden, founder of the Keyserlink Institute, a center for seed research and cereals cultivation in biodynamic agriculture, says: “We don't know yet how the development took place from grass to grain, from seeds that blow away as soon as they are ready to a seed head that contains the grains. And we also can't reproduce it yet.”

Open-pollinated varieties that are maintained through natural breeding methods and are not altered in laboratories require human guidance, according to Christine Nagel, a vegetable breeder with the organisation Kultursaat e.V. The knowledge necessary to do so has almost been lost, according to Nagel, and training programs for the gardening profession no longer exist. The development of a new variety that remains strong from year to year is a process based on the annual season cycle and the earth and requires 10 cycles of two years. In comparison, a hybrid variety is “finished” in two to six years.

The issue of funding is also important. So far, development of new varieties and preservation of existing true-to-seed plant types have been financed by associations and foundation assets. Sebastian Bauer from the Software AG Foundation emphasizes that the generous donations and exemplary level of commitment shown by organisations such as the seed fund of GLS Treuhand have enabled important developments in seed research and development. At the same time, support for this research must be brought out of the “charity niche”. “We have to see it as an investment in the future! Each market partner, and society itself, that is we as consumers, should be interested in making it possible for open pollinated varieties to be bred on a large scale.”

Stephan Illi, who served for many years as a board member with Demeter Germany, is also sure that solutions will only be found when all stakeholders are brought into relationship. Even in organic markets, more and more products are being sourced from highly specialized organic farms in Germany and abroad - from farmers whom neither the consumer nor the storeowner actually knows. Furthermore, many consumers, when they buy organically or biodynamically grown vegetables, believe that they are buying produce from 100 percent true-to-seed varieties. Consumers need more information. “At the same time, niches are developing, such as community supported agriculture or membership models, in which consumers make a strong, solidarity-driven commitment to farmers, and this enables higher quality and greater diversity. The consumers want to get involved, and we need to take advantage of this!”

The fellow train passengers had the idea of supporting crop seeds through a licensing fee on seeds as cultural assets. This could establish financially equal opportunities. This would require political action. Compensatory taxes were cited as a functioning example. In connection to seeds, one could imagine a licensing fee for those who today benefit from the processes that were carried out 10,000 years ago in Asia by humans and plants.

Organic farming: maintaining biodiversity and breeding for the local growing environment

Organic farming requires very high seed quality, as the specifications of different locations cannot and should not be levelled out by the use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides and fungicides. Every strain has a unique combination of traits, whether resistance against certain pests, adaptation to geographic circumstances, or taste characteristics. It is only thanks to this diversity that plants are able to adapt again and again, for example to changes in climate. Varietal diversity can only be ensured if politicians, industry, retail and consumers are all pulling together in one direction.

The Kulturgutexpress 2014, started on the occasion of the 90-year anniversary of biodynamic agriculture (Demeter), is an initiative of Vera Koppehel and Peter Daniell Porsche. Its mission is to create a “social sculpture” – a form of conceptual art developed by Josef Beuys – focused on the issue of seed preservation. Around 290 individuals and many initiatives participated in the train ride and the conference in May 2014, and they plan to continue the project to promote the vitality of seeds and agriculture on a cultural level.